| |

|

|

| |

Resident fish?

Tue 3rd June, 2014

|

|

|

|

A beautiful Bank Holiday weekend in Turangi especially the last couple of days. Once the heavy overnight frosts melted away it seemed more like late spring than early winter and Turangi was packed with families enjoying a very sunny Queens Birthday break. A beautiful Bank Holiday weekend in Turangi especially the last couple of days. Once the heavy overnight frosts melted away it seemed more like late spring than early winter and Turangi was packed with families enjoying a very sunny Queens Birthday break.

As expected the Tongariro received its fair share of attention but wasn't as busy as I thought it might be and I had no trouble finding places to fish.

If there are more people around I often avoid the pools and fish the less popular stuff in between. Its a tactic more anglers are adopting and over the weekend it proved again that you don't have to stand up to your neck in water or be able to cast a full fly-line to catch fish.

The latter part of last week saw some fantastic hatches along the river and I don't recall ever seeing so many birds "working" the water.

I was fishing a nice run during one of them and although I couldn't see exactly what was coming off, I guessed they were probably Deleatidium mayfly which are common on the Tongariro.

After tying on the appropriate nymph it wasn't long before the hunch paid off and I had a fish splashing at the rivers edge.

The overcast weather in between the rain and patchy drizzle that we had towards the end of last week was perfect for emerging mayfly.

The adult stages ... the dun and spinner have no functioning mouth parts, which leaves them prone to dehydration. Damp cloudy days lessen the chances of this happeneing but its not SO wet that it prevents their newly unfurled wings from drying. This enables the duns to fly to the safety of nearby foliage for their final moult into the mayfly spinner.

Creel Tackle House & Cafe {it was easier when it was just Creel Tackle ... but the coffee and sausage rolls weren't as good} have some good Deleatidium imitations. Steve the shops technical consultant and stock controller has already ordered in a selection of sizes in both the nymph and the soft hackle version which mimics the emerging nymph ... so pop in and give them a try.

Despite the holiday sunshine you can feel the water around your legs is noticeably cooler when you're wading, which is exactly what we need. Just to double check for you ... I went arse over tip into the river early on Monday ... and I can confirm that the water in my waders was bloody cold !

The frequency and size of the runs will continue to gradually build and there seemed to be a lot of jacks caught over the last few days, especially around town. This could be a pre-cursor for some better runs and with rain forecast next week the fish should pick up on any drop in pressure and get moving again as we head towards the weekend.

Last time I briefly mentioned "resident fish" ... like most anglers with the absence of any "official" data I've always just assumed there must be a resident population of trout in the river. But ever since I began fishing the Tongariro its something I've often wondered about ...does it include both species?...what are the numbers involved?... are they found throughout the Tongariro? ... why do they choose to stay in the river? Its a bit of a grey area and there is very little hard and fast information out there, probably because it would require a difficult and expensive study to discover the facts. So I decided to ask fishery scientist Michel Dedual if I was right in thinking that not every rainbow or brown trout returned to the lake after spawning ... and then later ... did he think there were fish of either species that spent their entire existence in the river?

I'd like to thank Michel for letting me reproduce those replies.

" Hi Mike,

Yes you are right not every rainbow (or brown) returns to the lake after spawning. The number of fish “deciding” to stay will depend on the food abundance.

Females invest about 25% of their weight in growing eggs meaning that after spawning they will need a really rich food supply to recover this 25% before growing more.

There are possibilities to do that in the rivers by feeding on invertebrates or juvenile fish but the task is far more difficult than recovering in the lake where, providing the food supply is plentiful, rainbows will quickly recover by preying upon smelt or bullies (when smelt are not abundant).

Even then our trap data shows that Taupo trout struggle to grow any bigger than they were when they spawned for the first time.

We don’t have any data on the proportion of lake fish remaining for a substantial time (the whole period between subsequent spawning) in the river but it is likely to be small for several reasons.

As mentioned earlier regaining in one year 25% of your weight relying on river preys will be a big task. Furthermore, that task will get more difficult for the large fish as they have to regain more weight.

One of the features of Taupo trout is that when in the lake they grow as quickly over winter as they do in summer. In fact they grow slightly quicker at the end of the winter when the productivity of the lake is at its peak. This consistent growth is good but it also creates a problem as we cannot detect any changes in growth that are apparent on the scales or otoliths that are used to age fish.

In the river the situation is different because the temperature and productivity of the river is far less in winter leaving a clear “winter” mark on the scales/otoliths that is visible in some juvenile fish that have spent their first winter in the river before moving to the lake.

However, in the adult scales and otoliths that we have observed we haven’t found any obvious winter mark that would attest that the adult fish has spent another winter in the river after the first spawning.

Resident trout are present in the system ... but resident doesn't mean they don’t go into the lake at all. Taupo rainbow originate from two different strains of rainbow in California. One strain is a typical coastal stream type where rainbow grow in the ocean and return to spawn in rivers.

The other strain comes from inland California, rainbows there are a more “resident” type spending their whole life in rivers. These two types are still present in the current population and are likely to stay.

There are scientific ways of quantifying the proportion of lake fish that stay in the river after spawning but the cost of such a study would be very difficult to justify."

In answer to my second question Michel replied:

" Well this is really hard to unequivocally demonstrate but in my opinion there are some fish of both species that spend their whole life in the river.

The first reason is that fish don’t HAVE to go to the lake to survive.

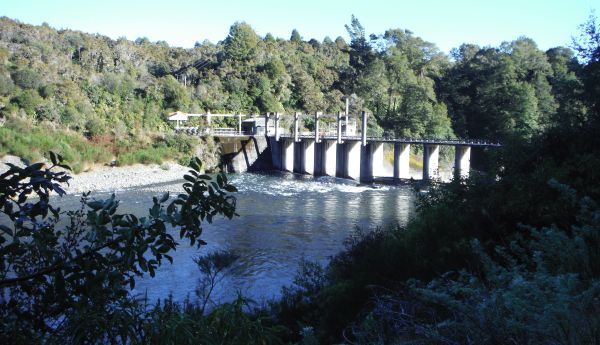

Another reason that makes me think this way is that upstream of the Poutu Intake (Begg’s Fall) there are resident populations of both brown and rainbow. Some of their progeny can move to the lake but obviously some have to spend their whole life in the river as the downstream migrant cannot return upstream of the Poutu Intake. I hope this will answer some of your questions."

Several references were made to scales/otoliths in Michel's reply. Most people know that they use scales to determine the age of a fish but they can also use other hard body parts like otoliths, the spine or tail bones. As a fish grows minerals and proteins absorbed from the surrounding water and the food it eats are constantly being laid down in its skeletal tissue. The under-side of a fishes scales and its otoliths { ear bones } }both contain groups of fine concentric rings that are usually compared with those found on a tree trunk.

Fish normally grow faster in summer and because of this the ring groups are well spaced out but as growth slows in winter the growth rings { called circuli } tend to get pushed together forming a much denser band. Fish normally grow faster in summer and because of this the ring groups are well spaced out but as growth slows in winter the growth rings { called circuli } tend to get pushed together forming a much denser band.

{ Michel pointed out that this isn't always the case while fish are in the lake, making it difficult for those tasked with reading the information on them.}

When illuminated under magnification these appear either as opaque or semi- transparent bands. A trained observer is able to interpret these patterns and the combination of one opaque zone and one transparent zone usually indicates one complete year of growth.

Scales have been used to age fish for over two hundred years but are generally thought to be the less reliable of the two because some fish can partially re-absorb their scales in times of stress, for instance during the spawning runs. At these times fish absorb protein from their bodies ... including the scales causing some of the rings to be less well defined.

A similar thing happens if scales are lost and then regrown and because part of the growth ring information has been interrupted the age of that particular fish could be underestimated.

The results are more accurate if you examine the otoliths these are resistant to re-absorption and of course outside damage. Unfortunately to remove them you have to sacrifice the trout.

All boney fish have three pairs of otolths situated in cavities behind the brain but cartilaginous fish such as sharks, skates and lampreys don't have them.

Otoliths are hard objects made up mostly of calcium carbonate deposits taken in from the surrounding water. This is the same compound that makes up things like marine shells. They're particularly useful to scientists because otoliths are the first calcified structures to appear as the fish embryo develops and contain a lasting record of what the fish has been up to since it hatched.

They're housed in hollow fluid filled chambers lined with hair like cells attached to nerve endings. Any movement of the otoliths stimulates the cells and helps the fish with orientation and hearing.

The sagittae are the largest of the three pairs and are the ones most often examined. The others ... the lapillus and ateriscii are much smaller and rarely used for the purpose.

Unlike fish scales the information laid down on a fishes otoliths is permanent and not as easily degraded or damaged. Unlike fish scales the information laid down on a fishes otoliths is permanent and not as easily degraded or damaged.

Nowadays with advances in the techniques and equipment used to analyze them scientists are convinced they can glean much more than just the age of a fish.

By studying the chemical markers otoliths contain they are now also able to tell when and where fish have traveled from the time they hatched ... invaluable information for fishery managers.

If you're interested click the link for a video showing the location of the otoliths in a rainbow trout.

Tight lines guys

Mike

www.youtube.com |

|

|

| Back to Top |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|